Goss’s Wilt Revisited. Will 2024 be a Challenge?

As you’re well aware, Goss’s Wilt is a relatively new disease in the northern states, other than in southern South Dakota, where it first appeared in 1978. Minnesota saw its first identified case in 2009, and North Dakota saw it in 2011. As an industry, we have responded quickly to this disease and made significant product progress in a relatively short period.

Before 2009, seed companies did zero screening for Goss’s Wilt in the early maturities. Many hybrids carried little to no resistance, and the disease showed up strong in 2012 with wall-to-wall corn grown across the Dakotas and Minnesota.

Before 2009, seed companies did zero screening for Goss’s Wilt in the early maturities. Many hybrids carried little to no resistance, and the disease showed up strong in 2012 with wall-to-wall corn grown across the Dakotas and Minnesota.

The robust disease presence surprised many of us, and we were forced to learn about it quickly. We also faced throwing away some hybrids with excellent yield but little or no tolerance to the disease.

Fast forward to 2024. It is impressive how far the industry has come regarding Goss’s Wilt. We are in great shape as we look at our new lineup and the genetic resistance levels that are now available. Average is no longer average! An “average” rating on a hybrid 10 years ago would be considered “poor” today.

What does all of this mean for farmers in our area?

- The material breeders are bringing out now is much improved. Everything in our lineup, from 74-day to 103-day, has been screened repeatedly for resistance. Even in northern North Dakota and Minnesota, products without resistance are not brought forward.

- Every hybrid has a resistance score! Scores of 8 and 9 can be found throughout the lineup, so you can be assured that resistant product options exist even in the most susceptible geographies. A 7 rating means the product has average resistance but should still handle 90+% of disease situations. A 6 means management should be taken if you know you have a known problem, but there are only four 6 ratings out of the 44 products.

- We do have one hybrid with a 5 rating, and not surprisingly, it is 16 years old! 13D91 is an 89-day conventional, and it really is older than the hills. But it is an excellent example of how our lineup has improved through the years. During D91’s heyday, most hybrids had similar tolerance and have since been eliminated. The challenge with removing this one is its high yield. It is still as good as it gets in our annual testing, and the disease is not present.

I bring this up because we have underestimated how much progress we’ve made against Goss’s Wilt in a relatively short time. As you finalize your hybrid selection, remember that everything you do today is leaps and bounds better than what was available 10 years ago.

My takeaways for the 2024 season

- We have not seen much Goss’s Wilt since 2020. With that said, we also have experienced three years of drought, meaning very few storms. When we return to more “normal” weather, I’d expect more instances of the disease, resulting in more plant damage.

- Inoculum levels should be extremely low region-wide, so I’d be surprised to see a significant outbreak this year.

- As referenced earlier, hybrids are so much stronger now that even if conditions are more favorable, I don’t expect the disasters seen 10 years ago.

Rick’s Key Notes on Goss’s Wilt

- Know your score! The first line of defense is hybrid genetics. While all hybrids can be infected, higher scores indicate an increased capacity to fight off the disease, protecting yields and minimizing losses.

- Rotation. Once Goss is in an area, getting rid of it is almost impossible. Rotation to non-hosts can reduce inoculum numbers present and reduce infections for future years.

- Tillage can be a helpful tool to manage corn residue and the bacteria present in it.

- Plant health is critical. Dialing in your fertility plan to ensure the plant has everything it needs will keep the crop healthy to fight Goss’s Wilt and other diseases.

- The disease only spreads from plant-to-plant through a physical injury, even with the inoculum present. Without wind damage, insect damage, hail damage or another type of damage, you won’t see a problem.

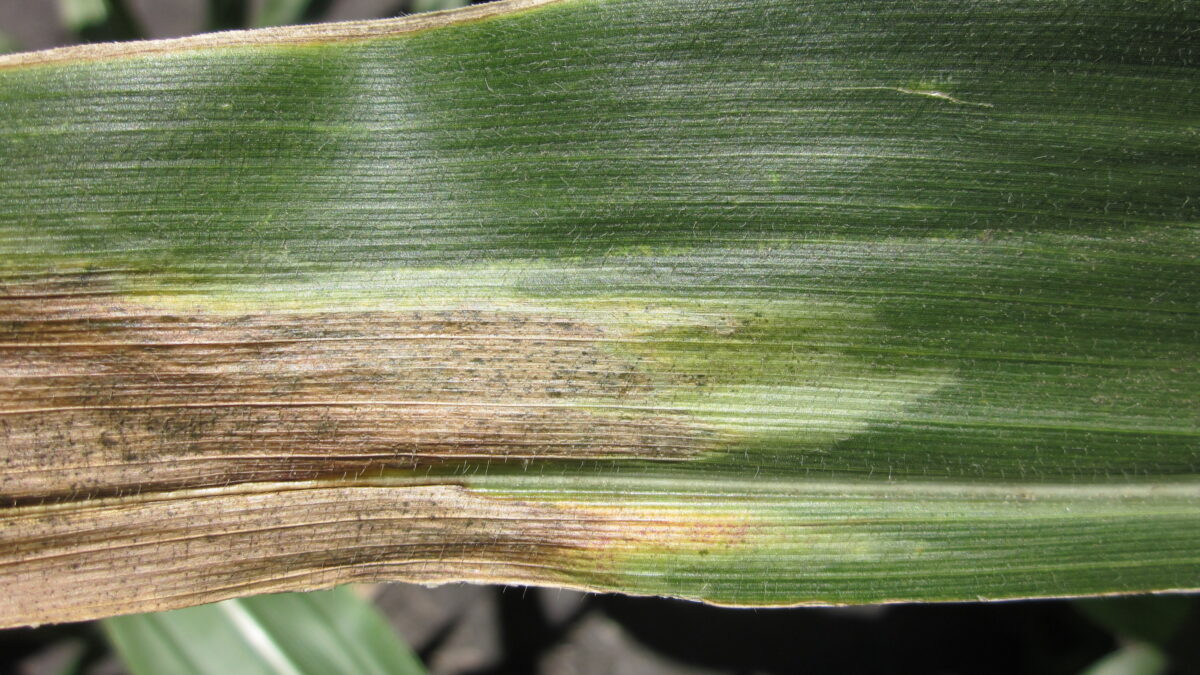

- We must get better at the identification of the disease. I believe it is being misdiagnosed, and in some cases, management decisions are made based on thinking the disease is present when it is not. Don’t throw a good hybrid out of your portfolio if you don’t have the disease. If you think you have a problem, confirm it by contacting one of us or sending a sample to your state diagnostic lab.

- Infections occurring in June or early July may cause yield loss. But if you don’t see infection until August or September, you don’t need to worry about yield loss. Make a note for next year.