Making the Case for Switching to Narrow Row Corn

“Rich on Agronomy” is an occasional agronomy column from Peterson Account Manager Rich Larson.

We’ve wrapped up the 2014 growing season, and it’s time to start planning for next spring. With lower commodity prices, you’re probably debating your next move for profitability. Increasing productivity and cutting costs are two factors you can control when trying to supplement lost income potential.

But cutting costs related to productivity is a slippery slope–how do you choose which costs to cut without negatively impacting yield? Basic fertility (N, P, K, and S) and proven hybrids should not be on the chopping block. In a down income year, increasing yields needs more attention than cutting costs.

You may not be thinking about adding any new paint, but if you do need to change planters and/or headers this year, you should also consider changing to narrower rows. Even at $3.00 corn, a 1,000 acre corn farm could see a $20,000-$40,000 income bump. As you will see, changing from 30″ rows to 20″ or 22″ rows has a positive effect on higher yields in North Dakota and Minnesota.

Corn row width has been the subject of extensive research in Iowa and Illinois for more than two decades. In that area, row widths of less than 30″ haven’t shown consistent advantages. For a while, we assumed the same was true “up north”, but we were mistaken.

Long-term research from the northern Corn Belt shows that corn prefers narrower rows by consistently producing higher yields at the same population. Most of the corn in our region is still planted in 30″ rows, but is trending toward 20″ or 22″ rows among growers who want to push the envelope on yield. Our longer days of sunlight are the generally accepted reason given for the positive yield response.

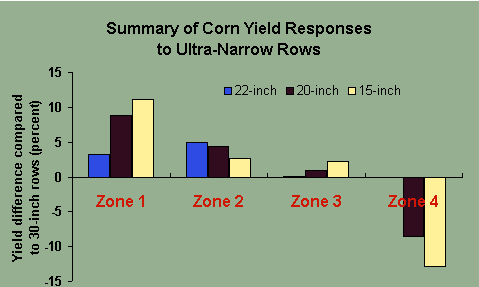

Purdue University evaluated the influence of narrower row spacing on corn grain yield throughout the Corn Belt, and the results are intriguing. The survey summary supports that the most positive yield effects due to narrower rows are found in the northern Corn Belt.

Zone 1 – north of I-90: MN, ND, and SD

Zone 2 – south of I-90 and north of I-80: northern IA

Zone 3 – south of I-80 and north of I-70: southern IA, northern & central IL, IN, OH, and PA

Zone 4 – southern IL and TN

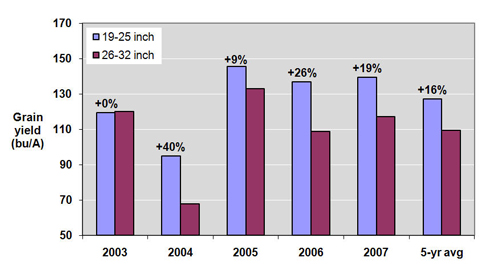

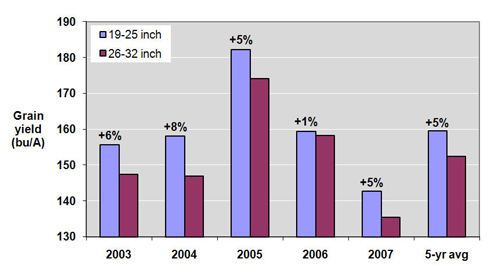

The following research from the University of Minnesota was conducted over 5 years in multiple locations at the same planted population. It is a consistent message and another “case in point” of why narrow row corn is a viable option to consider.

Growers in northwestern Minnesota increased yield by an average of 16% when corn was planted in 19″ to 25″ rows versus 26″ to 32″ rows. This was reported in the FINBIN Farm Financial Database over an average of 33 and 19 fields, respectively.

A bit farther south, growers in west-central Minnesota showed an average yield increase of 5% when planting corn in 19″ to 25″ rows versus 26″ to 32″ rows. (Source: FINBIN Farm Financial Database on an average of 46 and 180 fields, respectively.)

Data collected in southern MN did not show yield advantages with narrow rows, but the advantages climb consistently as you travel north.

Unfortunately, NDSU hasn’t studied row width extensively enough to evaluate, but data for MN and WI is consistent with data and feedback from ND growers who have made the move to narrow rows.

Other advantages come into play with narrow rows, some of which attribute to increased yield. If you use the same planter for both corn and soybeans, the narrower row width for soybeans may not boost yields, but the quicker canopy of both crops reduces weed competition. In corn, increased light interception by individual plants and less crowding of plants are key advantages. This is why you can push population a little more in narrow rows, pushing yields even higher with added fertility.

Consider this plan for your best ground: narrow rows; 35,000-36,000 plants per acre; and added fertility for the higher population. Be sure to include more than just N and P. High populations can cause decreased stalk diameter, so potash should be part of the fertility program, too.

You’ve seen the numbers and are aware of the advantages of the narrow row philosophy. Should you consider switching to narrow row corn? While I cannot answer that question for you, I can help you examine some of the anticipated investment costs. In Part 2, I’ll compare the cost of switching to narrow rows to the long-term increased return.

Call me if you’d like to talk more about a switch to narrow rows.