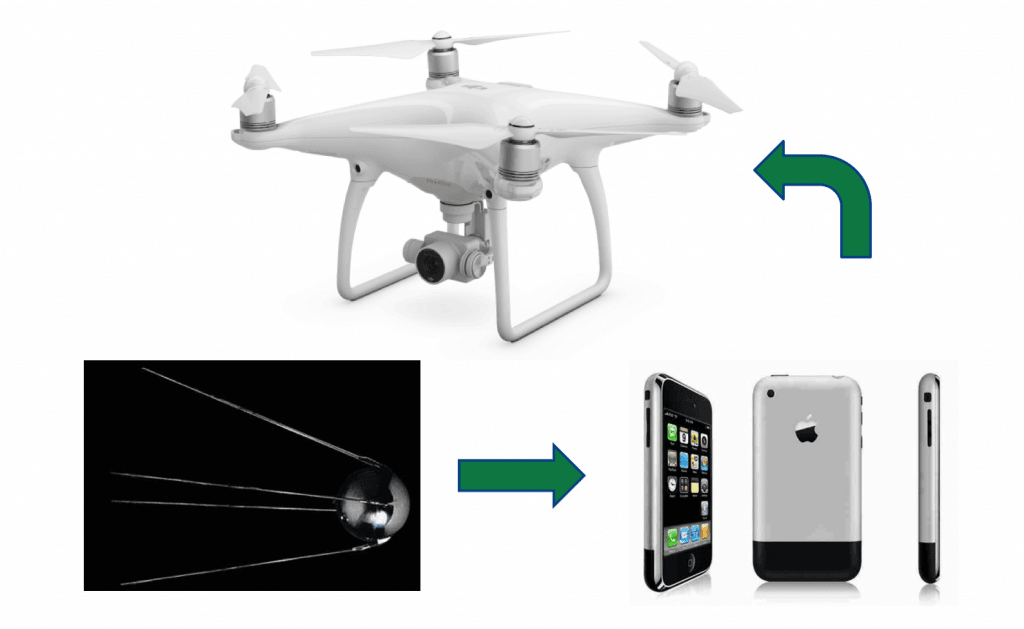

From Sputnik 1 to Phantom 4: UAVs Have Come a Long Way

These days, it seems like for every piece of technology that learn to use, a new version comes out right behind it. Precision ag technology, namely UAVs, is progressing more rapidly than anything we have seen before.

Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) are not a brand new technology: back in 1957, Sputnik 1 was the first successful satellite to orbit the earth. Today there are over 1,400 active satellites circling our planet with exponentially more technology and capabilities on board than when first introduced 60 years ago. It was only nine years ago when the first iPhone was released with a small GPS and an accelerometer on board. Today, nearly everyone has a phone in their pocket that can do everything from giving street-level directions to counting your steps to unlocking your car with the touch of a button.

The decades-long development of satellite and communication technologies have helped lay the foundation for many of the recent advancements in UAV technology.

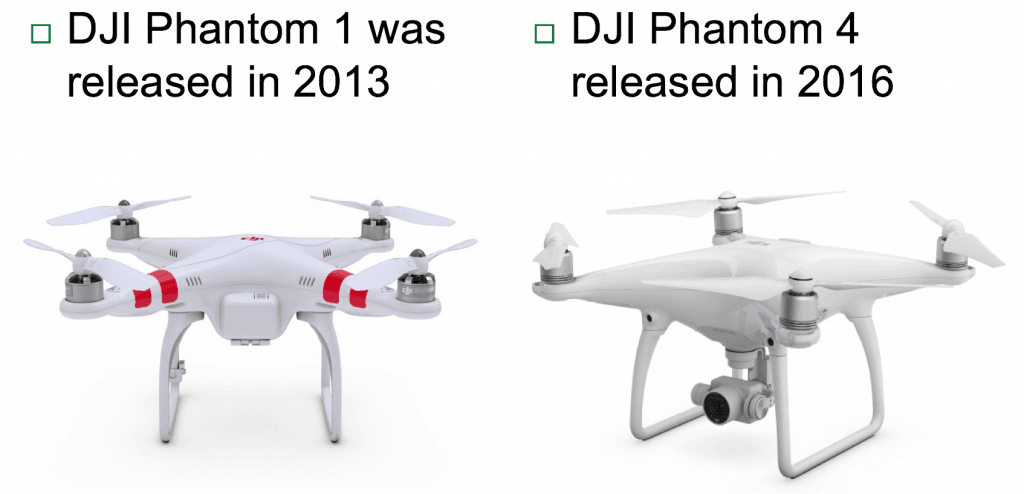

Just three years ago, a company named DJI introduced its flagship UAV, the Phantom 1. This past spring their newest piece of technology, Phantom 4, was released.

The level of technology packed into the Phantom 4 blows away the Phantom 1, even though it was introduced a short three years ago. Technology is moving so quickly that farmers need to pay close attention so that they can ensure they don’t miss advancements that can help us grow a bigger and better crop.

One recent advancement is the capability of smaller, less expensive UAVs to map fields much like the larger, more expensive, fixed-wing units have been doing for a few years. The smaller units have the advantage of ease of use as well as safety.

Another significant recent advancement is the release of affordable calibrated multispectral sensors.

These sensors, with calibrated images, allow farmer’s maps to be compared over time. Because uncalibrated images can only be compared to themselves, these new maps allow farmers to track plant stress, diseases, and nutrient deficiencies over a period of time.

Multispectral imagery has the potential to detect N deficiency before our eyes can see it. When utilizing hot streaks in our fields, we can use the multispectral imagery in-season to gauge if the rest of our field shows signs of deficiency compared to the N hot streak. In the past, symptoms would need to be visible to the naked eye, which means the damage had already occurred. With the calibrated multispectral technology, farmers are able to detect and react earlier – thus preserving yield.

Through each advancement, the opportunities for turning precision into decisions increases. Keeping up with technology is no easy feat, but with a little research and time, you can make sure you have access to tools that can help increase your yield and make your job a little easier.