Sudden Death Syndrome: Stack Management Strategies for Best Defense

Sudden Death Syndrome (SDS) is a soybean disease caused by a fungal pathogen. More common in south and central Minnesota, SDS is creeping into fields in northern Minnesota, eastern North Dakota, and a handful of counties in South Dakota.

University of Nebraska-Lincoln Plant Disease: Sudden Death Syndrome (SDS) | CropWatch (unl.edu)

Infection

Sudden Death Syndrome can infect plants early in the season through later vegetative growth stages. Shortly after germination, the fungi infect seedling roots where it will remain asymptomatic until later in the season. When plants approach late reproductive phases and seed fill, visual symptoms will begin to appear as toxins move from the fungi in the roots to the leaves. August is a good time to begin scouting for symptoms.

Identification

SDS can easily be confused with brown stem rot (BSR) and stem canker. However, BSR and stem canker only infect the stem, while SDS will damage both aboveground tissue and the roots. Additionally, SDS normally shows symptoms earlier in the season than BSR.

When scouting areas where you suspect BSR or SDS, split the stems of damaged plants. Both diseases can cause stem rot, but SDS will leave the pith white, while BSR will cause a brown center. If the central pith remains white, examine the roots to confirm SDS.

University of Nebraska-Lincoln Plant Disease: Sudden Death Syndrome (SDS) | CropWatch (unl.edu)

Martin Draper, USDA-NIFA Plant Disease: Sudden Death Syndrome (SDS) | CropWatch (unl.edu)

SDS causes root rot that eats away at the laterals and taproot. Plants affected by root rot will pull out of the ground easily. If plants are dug up rather than pulled, rotting roots will be brown and mushy instead of healthy white. In advanced stages of SDS, you might be able to spot blue-ish mold on the outside of the taproot.

E. Byamukama, SDSU Sudden Death Syndrome Starting to Develop in Soybeans (sdstate.edu)

Factors Favoring Infection

Cold, wet soils for two to four weeks after planting are conducive to SDS infection. These conditions slow seed germination and emergence and widen the window for infection. Compacted soil and poor drainage also encourage infection.

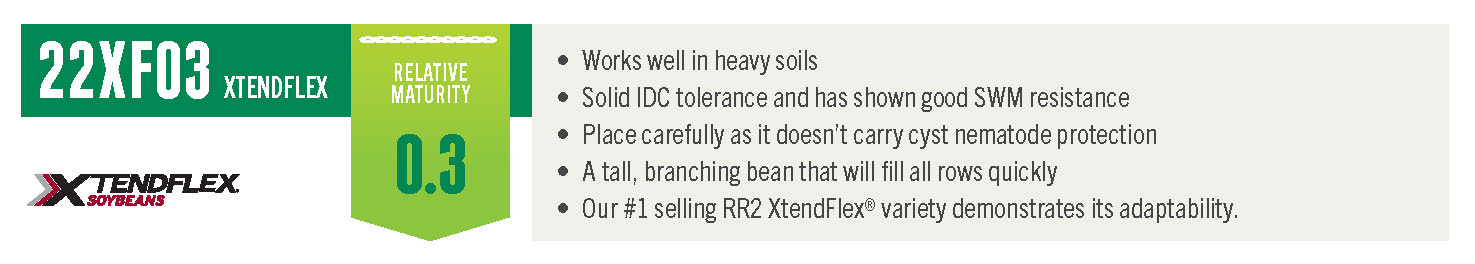

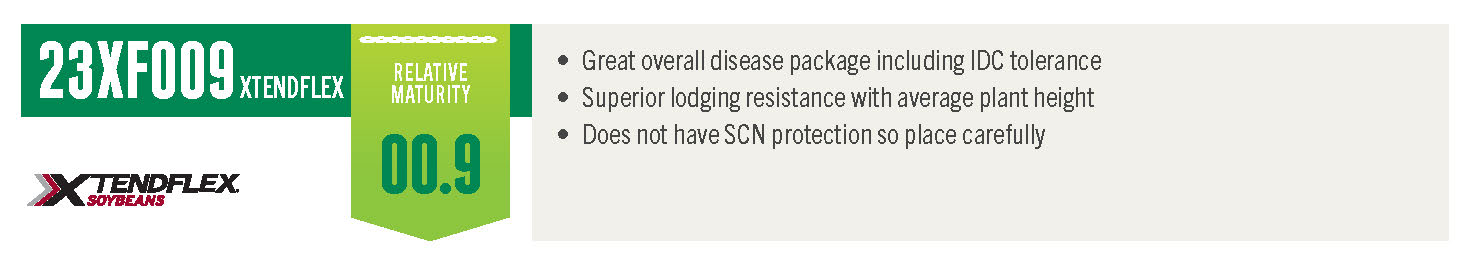

Additionally, there is a correlation between high soybean cyst nematode populations and risk for SDS infection. SCN weakens plants, and SCN root wounds offer an entry point for the fungus.

Management

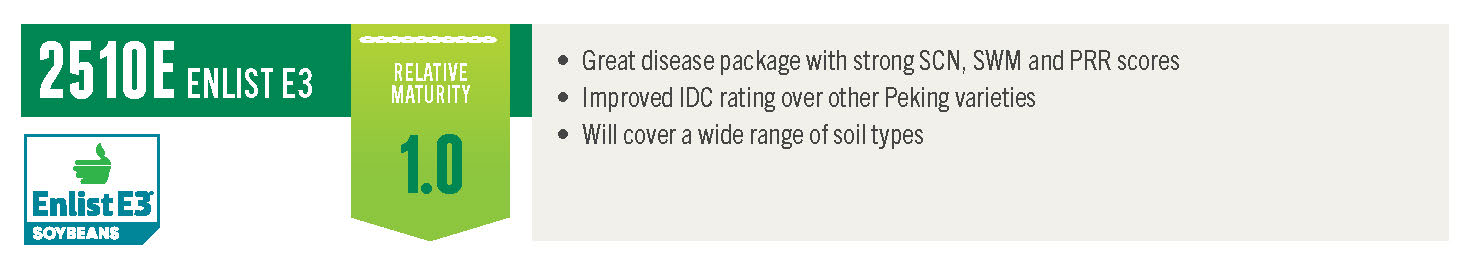

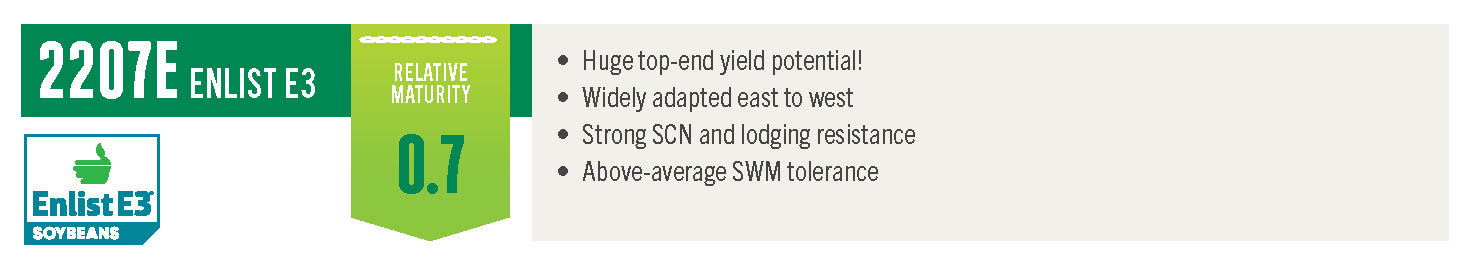

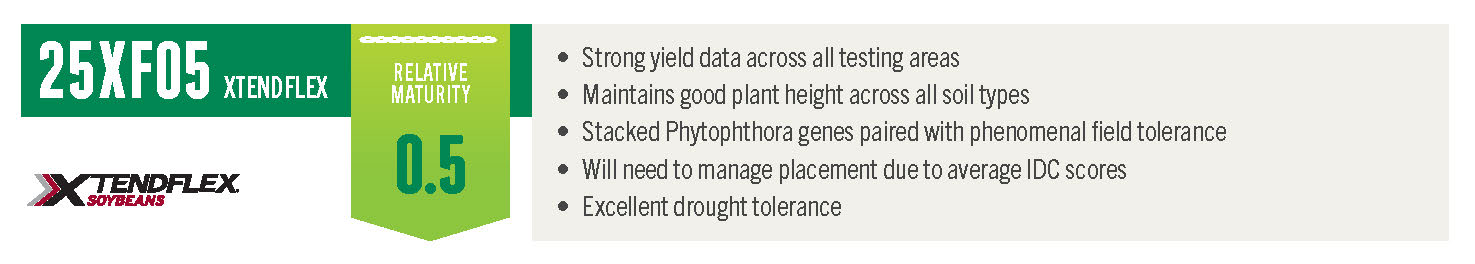

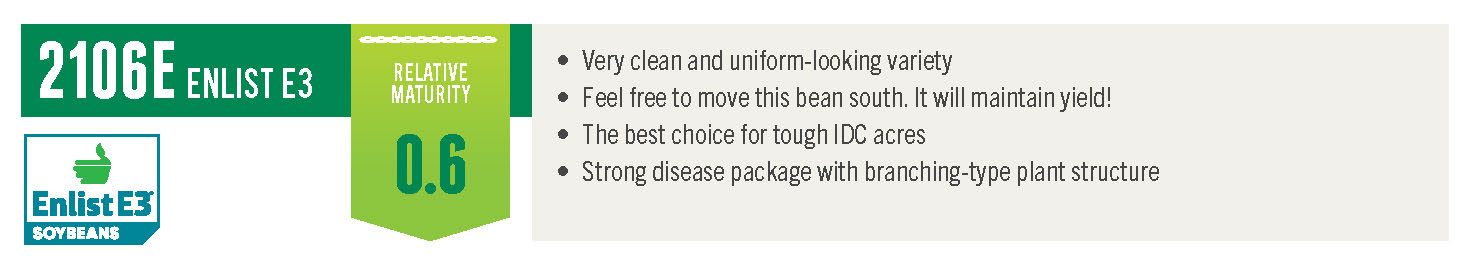

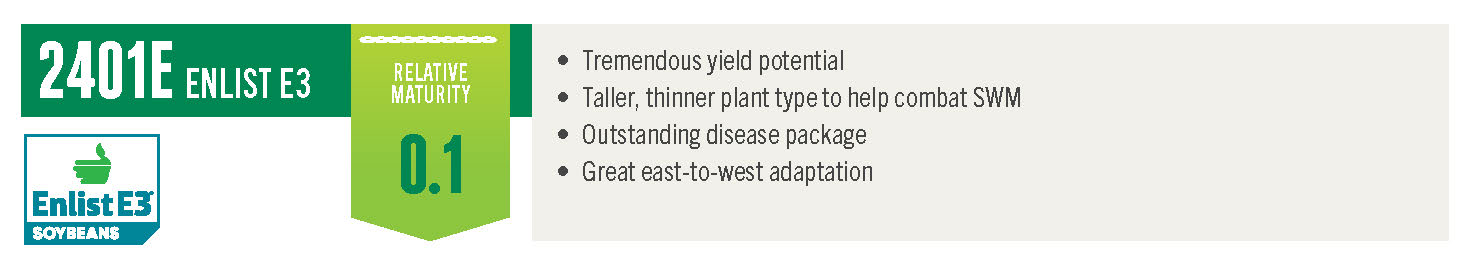

The strongest management tool is genetic resistance. More and more genetic suppliers are working on building resistance to SDS as it spreads into new maturity zones. If you are in a high-risk area, we recommend stacking a high-tolerance SCN gene with SDS tolerance for the best protection.

While not an option for everyone, delaying soybean planting until soils are warmer (>55 deg F) also lowers the chances of infection. This is especially important in fields with a history of SDS. Early planting into cold soil heightens infection potential not just for SDS, but many other diseases.

This disease can winter on soybean and corn residue, so to be effective, crop rotations must be lengthened and include other non-host broadleaf and small grain crops.

Foliar fungicides are ineffective and success with fungicide seed treatment is limited. A recent study from the Crop Protection Network found only two active ingredients that had some control over SDS, pydiflumetofen and fluopyram. The study can be found here. (Crop Protection Network)

SDS can cause dramatic hits to yield and is difficult to manage, but stacking management strategies will give you the best shot at protecting your yields.